John Baskerville: The Anatomy of a Type Part II

While John Baskerville introduced many improvements to the art of printing, he did not profit by them. Standards of production were so high that he was unable to compete with the commercial printers for the work of the booksellers, who complained that his prices were two to three times as much as they could reasonably be expected to pay for similar work.

In 1762 Baskerville wrote to Benjamin Franklin about his problems in trying to maintain his printing office: “Had I know other dependence than typefounding and printing, I must starve.”

During the remainder of his life he made a number of fruitless attempts to dispose of his punches and matrices, along with the rest of his printing equipment.

It was not until 1779, four years after Baskerville’s death, that his widow was able to find a purchaser, in the person of Caron de Beaumarchais, the French dramatist, who had engaged to publish an edition of Voltaire. When this work, 70 volumes in octavo and 92 volumes in duodecimo, was off the press at Kehl, Germany in 1789, Beaumarchais took the punches and matrices to Paris, where he established a typefoundry.

Following his death in 1799, the punches went through many hands until 1893 when they became the property of the Bertrand Typefoundry in Paris, although their origin was unknown to the purchasers.

Rogers and Revival

The revival of the Baskerville types in our own time was prompted by the distinguished American typographer, Bruce Rogers. While serving as advisor to Cambridge University Press in 1917, Rogers discovered in a Cambridge bookshop a specimen of the type, which he traced to the Fonderie Bertrand. When he became printing advisor to Harvard University Press in 1919, he recommended the purchase of Baskerville types for use at the Press.

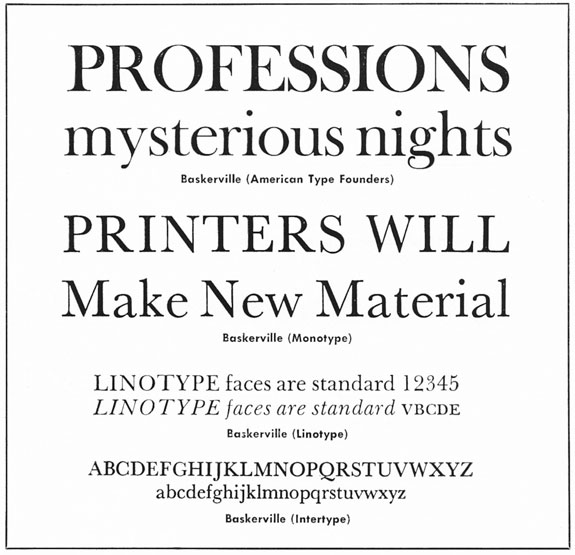

When the Monotype Corporation of London—entered its program of reviving a number of classic roman types, Baskerville was one of the first to be considered. It was cut in 1923. The American Monotype firm offers the same recutting. In 1926 the Stempel Typefoundry in Frankfurt, Germany produced a copy, which was also used for the German Linotype company a year later. Mergenthaler Linotype in England and the United States brought out a version in 1931, the same year that Intertype Baskerville also became available.

In 1954, the Paris foundry, Deberny & Peignot, which had become the owner of the original punches through purchase in 1936 of the Bertrand firm, offer an authentic rendering, made from the same punches.

With such accessibility, it didn’t take very long for Baskerville to be one of the widely used types. The Fifty Books of the Year exhibitions offer an excellent index of favorable reception. Making its first appearance in the show in 1925, it has been absent from the annual list just once, in 1927. In three different years, Baskerville has been used in 15 selections out of the annual 50, and is now the leading type, having been used through 1967 in 296 books selected to appear in the show.

In a most generous action, M. Charles Peignot, representing the firm of Deberny & Peignot, return Baskerville’s original punches to English soil in 1953, as a gift to Cambridge University Press, which accepted them as a national heritage.

The Baskerville types discussed up to this point have been the originals were very close copies, but there is another Baskerville, well-known and deservedly popular, and Sibley as a display type. In Europe this version is called the Fry Baskerville, while in the United States it is more commonly known as foundry Baskerville.

In 1764 Joseph Fry and William Pine opened a typefoundry in Bristol, England, under the direction of a punchcutter named Isaac Moore, whose name was given to the firm. Moore cut a copy of Baskerville’s letters, the first showing of it appearing in a 1766 specimen sheet of the foundry.

Two other founders of the period imitated the Baskerville design, Alexander Wilson in Glasgow, Scotland, and the Caslon foundry in London. It is the Fry cutting, however, which has come down to the present through the circumstance of changing ownerships and various foundries, culminating in the punches becoming the property of the firm of Stephenson Blake, which re-issued the type in 1910. In this country, American Type Founders brought out the same face about 1915 the cutting devised by Morris Benton.

Foundry Baskerville is at its best in the larger sizes, being a trifle thin below 18-point. It did not receive very much attention until it became a “trend” type in national advertising about ten years ago. Since that time it has seen frequent use and has been stocked by most of the typesetting specialists. There is even a photo-lettering version called Baskervale.

The recognition factors of the Baskerville style are fairly easy to remember. The cap E features a lower horizontal arm that is considerably wider than the upper arm; the Q has a long, sweeping tail; the R features a wide straight tail; and top of the T is quite flat. The simplest method of determining the Linotype version from that of the Monotype is by examination of the T. The Lino copy is slightly concave.

In the lowercase, the most easily recognized letter is the g with its unclosed lower bowl. The Monotype Italic has a number of distinctive features. The letters J, K, N, T, Y, and Z feature the decorative or swash characteristics. No standard forms of these letters are available. In the slug versions, the ordinary italic caps are standard.

The basic difference between the original Baskerville and the foundry, or Fry, imitations is in serif structure, which in the latter is almost needle-sharp, as opposed to the flat endings of the former. In addition, the foundry type has much greater contrast between thick and thin strokes.

Generally, in the United States, the foundry type is used for display, since the American Monotype firm does not manufacture the type larger than 36-point, although the English company carries the range through to 72-point.

With the many fine roman types presently available, the continuing popularity of this 18th-century English type is justification indeed that its creator labored in a good cause.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the March 1968 issue of Printing Impressions.